A little while ago, I was asked to give a presentation to CEOs on outsourcing. The audience wanted to know about adopting outsourcing for their companies; making use of its promise while avoiding its pitfalls. It seemed to me (unimaginatively, I must admit) that the whole thing boiled down to four fundamental questions - the why, the what, the who and the how.

I decided to expand the presentation into a series of blog posts, one per question.

The Who Question

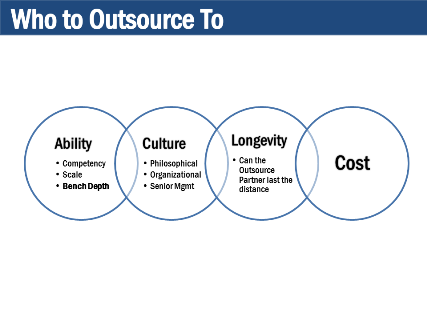

Once you've clarified why you're looking for an outsource partner and also which pieces to outsource, you're faced with the next big question – who? What should you look for in your potential outsourcing partner? The choice, I put to you, comes down to four linked characteristics.

Ability

The first characteristic, of course, is ability. A vendor cannot be under consideration at all if the basic ability to handle whatever you plan to outsource is not present. This is not always an easy thing to judge, especially if the field of potentials is small. Having a good idea of what you are outsourcing is very useful here, because the choices often boil down to relatively narrow judgements.

The first thing to judge is competency – are all the skill sets present with the vendor, and has the vendor any demonstrated track record in the skills and business areas required. In case vendors do not have the exact skill sets required, they should at least have exposure to the industry or expertise in the underlying technology.

Next, the vendor should have the scale of operations that match your needs, both geographic and numerical. Geographic scale is important; choosing a local vendor for nationwide requirements may cause bottlenecks, while a national player may not be the best choice against more specialised vendors if the need is regional. Numerical scale is the size of a vendor's balance sheet, the number of people it employs – all these should match the scale of operations you have in mind.

Finally, there's the business of bench strength; if there is one thing in the process that causes one's neck to hurt, it is this – hence the bold lettering on the slide. Companies may have credentials and skills, but when time comes to execute the contract, finding individuals to fill roles becomes a long and painful exercise. There is usually no problem at junior levels, but usually when choosing an outsource partner you want more than just bottom-level skills in large numbers; you want specialists. Outsourcing development requires architects, designers, project managers; outsourcing infrastructure requires networking specialists, security experts, database gurus - these are the ones that prove troublesome.

The bench problem is likely to persist; specialist skills are unlikely to ever become plentiful and outsource partners are thus always going to have to juggle demand for them. The other problem I face, in my previous avatar on the supply end of outsourcing, was experienced people are often deployed with a previous customer who is loth to let the skill go, even if under-utilised. Conversations where you want to replace good resource with a less experienced one because someone else needs it, is never going to be among the more pleasant ones.

At the same time, preferred outsource partnership contracts take a long time to negotiate. No vendor is going to identify and reserve high quality resources for you in advance and wait; the best bet is to ask for the top few key resources to be named at the time when the final contract is being signed (usually that takes a month or two, which is usually a good enough lead time for this) – this is when the outsource partner has maximum incentive to find good people. Reality is – no matter how sincere the partner - this incentive will drop a little after the contract is signed.

Culture

What holds a successful company together is often this secret sauce called culture. One of the greatest challenges of any outsourcing contract is – you are asking a large number of people to now do tasks that internal employees previously did, but this outsource team is from a different culture. This is a bigger problem if the work is done on-premise, since the cultures now have all the proximity they need to clash noisily.

Do not underestimate the culture problem. Cultures are often deep, and very tribal; they do not easily accommodate alternatives. The challenge of large scale outsourcing with a single partner is not unlike the challenge of a merger; there too one has to deal with a sudden influx of people with a different way of working. If misaligned, this will lead to conflict (sometimes, in my experience, even to fisticuffs) and certainly to missed results and loss of productivity.

Usually, the vendor is asked to lose the culture war, to adopt the culture of the outsourcing company. I've learned the hard way that this is usually a mistake; companies inculcate cultures deep into their employees and it will not disappear overnight by contract or fiat. I feel two things are required – first, choose a company whose culture broadly matches yours, and two – be ready for some give and take. One should absorb the best of the outsource partner's culture – and give up some of the poorer features of one's own. This isn't the compromise it sounds like – company cultures are geared to enhance a core strength; the outsource partner should thus have a culture better suited to efficient management of technology than the company itself.

Longevity

Long term is an overused term, but there usually is something beyond the long term. One may choose an outsource partner for strategic, tactical or any other reasons nut no one wants to repeat this process frequently. The underlying assumption to such an outsourcing contract is that it will be around for a while – this makes the negotiations, the cultural adaptation, the huge amount of process change that invariably accompanies such transitions all worthwhile. Without implicit or explicit commitment to the long term this exercise not worth the effort; one should stick to project-wise contracts with whichever vendor is available at that time.

Its always difficult to predict what will happen a decade hence, but one should nevertheless try and identify partners that are likely to be around for that long. This is not related to size, though too small a size usually makes things riskier. It is somewhat easier to identify companies that may not be around rather than ones that may – market intelligence, bleeding balance sheets, takeover targets, all these may indicate companies that are soon to change ownership, change businesses or go under entirely.

Cost

The last reason is obvious enough, there's little I can add here.

Great treatment of this wonderful subject, feel there is no article online then this!Vendor Contract Template

ReplyDelete